H- pylori

H. pylori – The Gut Bacteria You Shouldn’t Ignore

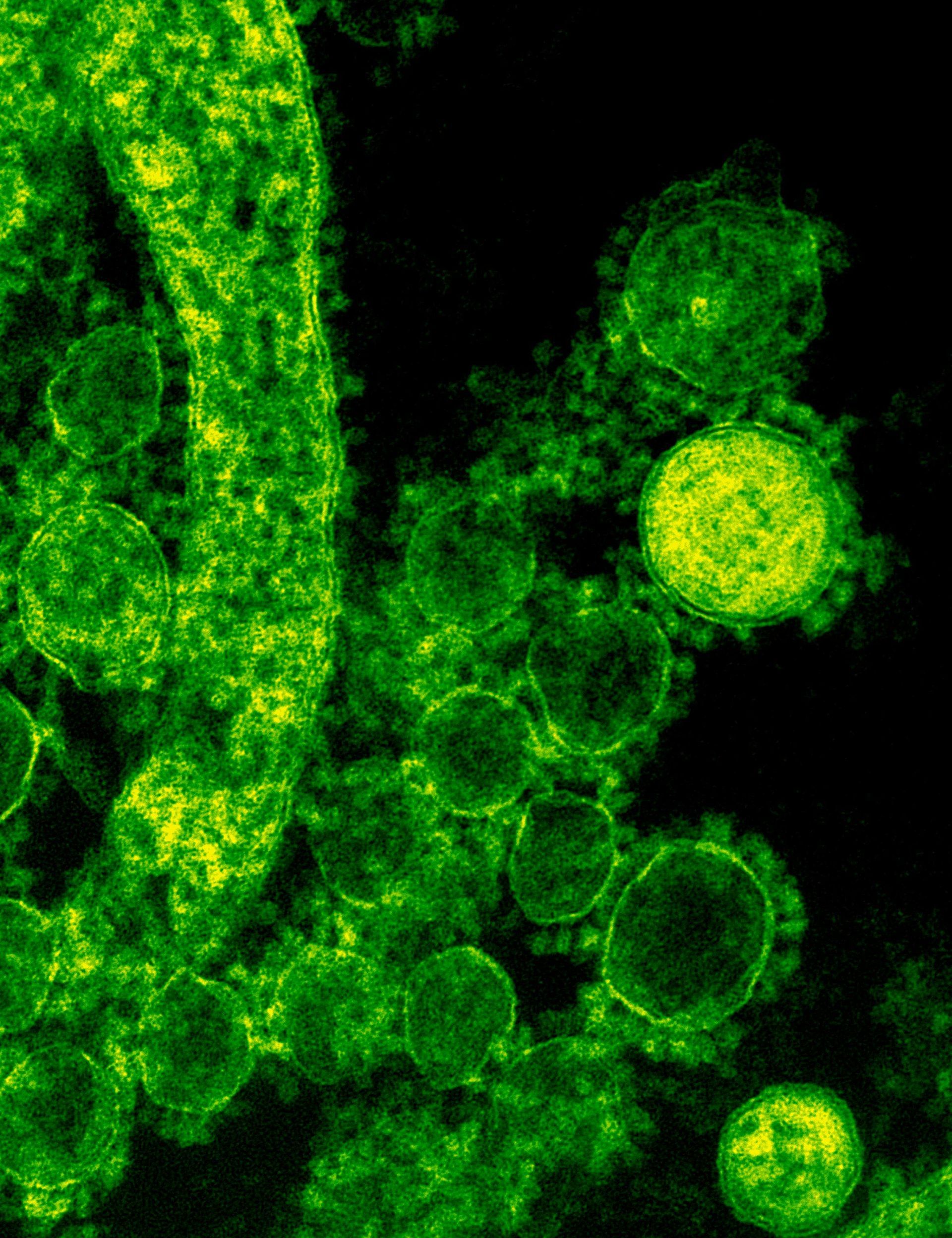

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped bacterium that lives in the stomach lining. It is one of the most common chronic bacterial infections in the world—yet many people who carry it have no idea they’re infected. While it can quietly persist for years, untreated H. pylori can cause chronic inflammation, peptic ulcers, and in some cases, even lead to gastric cancer.

This bacterium is well-adapted to survive in the harsh, acidic environment of the stomach. It releases an enzyme called urease, which converts urea into ammonia to neutralize stomach acid around it, allowing it to evade destruction. Over time, this localized damage to the stomach’s protective mucous layer can trigger inflammation, change stomach acid levels, and disrupt digestion in significant ways.

H. pylori is typically transmitted through contact with contaminated food or water, poor hygiene practices, or person-to-person exposure through saliva. It is most often acquired during childhood, particularly in areas with overcrowded living conditions or limited access to clean water and sanitation.

Once infected, symptoms may not appear right away. In fact, some individuals never experience noticeable symptoms. But in others, especially as the infection persists or spreads throughout the stomach lining, it can cause vague but progressive digestive complaints. These may include bloating, upper abdominal discomfort, frequent burping, nausea, and early fullness after eating. Some individuals lose their appetite or begin losing weight unintentionally. As the infection worsens, pain may become more noticeable, especially on an empty stomach. In some cases, ulcers may develop and bleed, leading to symptoms like fatigue, black stools, or iron deficiency anemia.

In its early stages, H. pylori may even stimulate acid production, especially in infections limited to the antrum of the stomach. This may contribute to duodenal ulcers and increased acid sensitivity. But over time, particularly if the infection spreads to the body (corpus) of the stomach, acid production often declines. This can lead to a condition called hypochlorhydria, or low stomach acid. This shift has multiple ripple effects on digestive health. With reduced acid, proteins aren’t properly broken down, mineral absorption—especially of iron, calcium, zinc, and magnesium—declines, and vitamin B12 absorption becomes impaired. The loss of acidity also allows for harmful bacterial overgrowth in the upper GI tract, and impairs gastric motility, contributing to gas, bloating, and maldigestion.

Surprisingly, low stomach acid from H. pylori can also trigger or worsen gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). As food stagnates and pressure builds in the stomach, the risk of acid or bile reflux into the esophagus increases. Over time, this can damage the esophageal lining, possibly leading to erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, or—in rare cases—esophageal cancer.

Several serious health conditions have been linked to chronic H. pylori infection. These include peptic ulcers, both gastric and duodenal, as well as chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy, and even a type of stomach lymphoma known as MALT lymphoma. Persistent inflammation of the stomach lining also raises the long-term risk of developing non-cardia gastric cancer. Additionally, chronic H. pylori infection can impair iron and B12 absorption, contributing to unexplained anemia or fatigue.

Accurate testing is essential for proper diagnosis. The urea breath test is one of the most reliable and non-invasive methods. It detects the presence of urease produced by the bacteria in exhaled breath. Stool antigen testing is another effective method, particularly useful for both diagnosis and follow-up after treatment. Blood antibody tests are available but are less helpful after treatment, as antibodies can remain elevated even after the infection is gone. In some cases, especially when ulcers or bleeding are suspected, an upper endoscopy with biopsy may be necessary to directly visualize and test the stomach lining.

If H. pylori is confirmed, treatment is both necessary and effective. Standard therapy involves a combination of two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), often referred to as triple therapy. In areas where antibiotic resistance is high or after previous treatment failure, quadruple therapy is used, adding a bismuth-containing compound such as Pepto-Bismol. Treatment typically lasts 10 to 14 days and may cause temporary side effects like nausea or a metallic taste. Due to rising resistance, certain antibiotics like clarithromycin may not work as well in some regions, and in such cases, alternative regimens guided by susceptibility testing or regional guidelines are recommended.

After completing treatment, it’s important to confirm eradication, usually with a urea breath test or stool antigen test at least four weeks after therapy. Blood antibody tests are not useful for this purpose.

Prevention of H. pylori infection centers around good hygiene practices. This includes washing hands thoroughly before meals and after using the bathroom, drinking only clean or treated water, and ensuring food is prepared and stored safely. Avoiding sharing utensils, especially in areas with high infection rates, may also reduce the risk of transmission.

Although H. pylori is common, it is not harmless. Its effects on the stomach lining, acid production, nutrient absorption, and risk of ulcers or cancer make it a bacteria that should not be ignored. With appropriate diagnosis and treatment, most infections can be successfully cured—restoring digestive function and reducing long-term health risks.